© Professor Carly Stevens

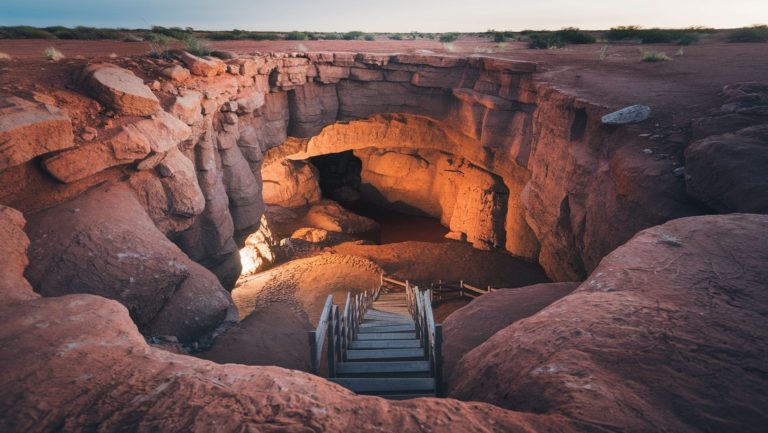

Fifty years of change on iconic limestone pavements has revealed mixed fortunes for one of the most distinctive landscapes in the UK.

The landscapes – which will be familiar to visitors to the Yorkshire Dales and fans of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows film – have, in many places, seen reductions of specialist species and more common less desirable species become more abundant.

However, it is not all bad news as the picture is very mixed across the UK’s areas of limestone pavement with some areas increasing in plant biodiversity.

The findings, which reveal large changes since the 1970s, are from the first national assessment in half a century of plants and vegetation in Britain’s rare and iconic limestone pavements, which was conducted by Carly Stevens, Professor of Plant Ecology at Lancaster University.

An internationally important habitat, Britain’s limestone pavements are predominantly found in the northern English counties of Yorkshire, Lancashire and Cumbria, as well as in North Wales and Scotland.

Plants, such as ferns and herbaceous species more commonly found in woodland, heathlands and grasslands, grow within the deep gaps and cracks in limestone pavements known as grikes, often creating a hidden world that you cannot see until you stand directly above them.

In the early 1980s laws were introduced to protect limestone pavement from quarrying, and many areas are now covered by nature reserve status.

However, despite being a rare and treasured landscape feature, and habitat to many specialised plants and wildlife, Britain’s limestone pavements have undergone few scientific studies.

To help address this, Professor Stevens repeated a limestone pavement survey undertaken by two scientists (Stephen Ward and David Evans) in the early 1970s.

Professor Stevens used the same methods to replicate the 1970s study as best as possible, surveying areas of limestone pavement totalling 3157 hectares across five years between 2017 and 2022.

Her study, which is published in the academic journal Functional Ecology, recorded 313 plant species across UK limestone pavements – an additional 29 species on the number recorded in the 1970s.

And some pavements saw the number of plant species living there, or species richness, increase.

However, despite many areas falling under the protection of nature reserves, some less desirable species, such as thistles, nettles and bracken, have increased in abundance across different limestone pavements in the UK. And Professor Stevens also found that important specialist species, such as primrose, lily of the valley, elder flower trees and hairy violet, have declined in abundance across UK limestone pavements.

However, these declines were not uniform and some of these species did see increases in some areas – adding to a complex, but important picture that will be invaluable information for conservationists.

“Limestone pavements have undergone large changes in the number and types of plants that live in these rare and spectacular habitats,” said Professor Stevens. “Limestone pavements are a habitat of high conservation value and they are protected for their unusual geology and the plants and animals that live in them.

“But if we are to conserve them for future generations, it’s important to understand why these changes have occurred.”

A major factor appearing to affect some limestone pavements is tree cover. Professor Stevens undertook aerial photography comparisons with historical aerial images for all the limestone pavements in England to compare how the number and size of trees had changed.

She found that some pavements had seen their area shaded by trees increase by more than 50%. Despite this the number of pavements without trees also increased, showing there’s a very mixed picture across different areas – often depending on the number of trees in the surrounding area.

Pavements where the numbers of trees and shrubs increased have commonly seen reductions in plant biodiversity. Professor Stevens believes this is probably due to trees and shrubs blocking off the light for smaller plants in among the grikes. Those pavements most affected by tree cover are found in Lancashire and Cumbria.

Those pavements that have low or moderate tree cover are more likely to have seen increases in species richness – though not necessarily with desirable specialist species.

Professor Stevens found many open pavements were impacted by grazing of animals, though there have been changes in the 50 years between surveys.

“Grazing pressure has declined in a lot of areas since the 1970s as a result of agricultural policy but there are still some pavements that are overgrazed,” said Professor Stevens. “Grazing can be an important tool in the management of limestone habitats but it needs to be carefully considered as overgrazing can result in a loss of biodiversity. Similarly, under-grazing can result in scrub and tree encroachment, which we see can also affect diversity and species composition as light levels are reduced.”

The survey will help to inform the future management of limestone pavements, an area that is still developing and will benefit from the survey results and additional data.

“At this stage we don’t actually know what optimal management looks like for limestone pavements,” said Professor Stevens. “This survey provides vital data to help further understanding on what the current picture is for limestone pavement vegetation. However, we still need more research to help improve our knowledge on what the threats are to habitat and the potential for restoring damaged limestone pavements.”

The study is outlined in the paper ‘Large changes in vegetation composition seen over the last 50 years in British limestone pavements‘.

Professor Carly Stevens on limestone pavement in Lancashire

Back to News